portable energy solutions for pastoral nomads

energy & rural technology program officer, iird

chamba district, himachal pradesh & Gurdaspur district, punjab

India is home to many nomadic indigenous groups, with an estimated migratory population of about 80 million people. Nomads face unique challenges; without a permanent home, they cannot access electricity, piped water, education, or healthcare. This project sought to identify portable solutions to improve access to energy.

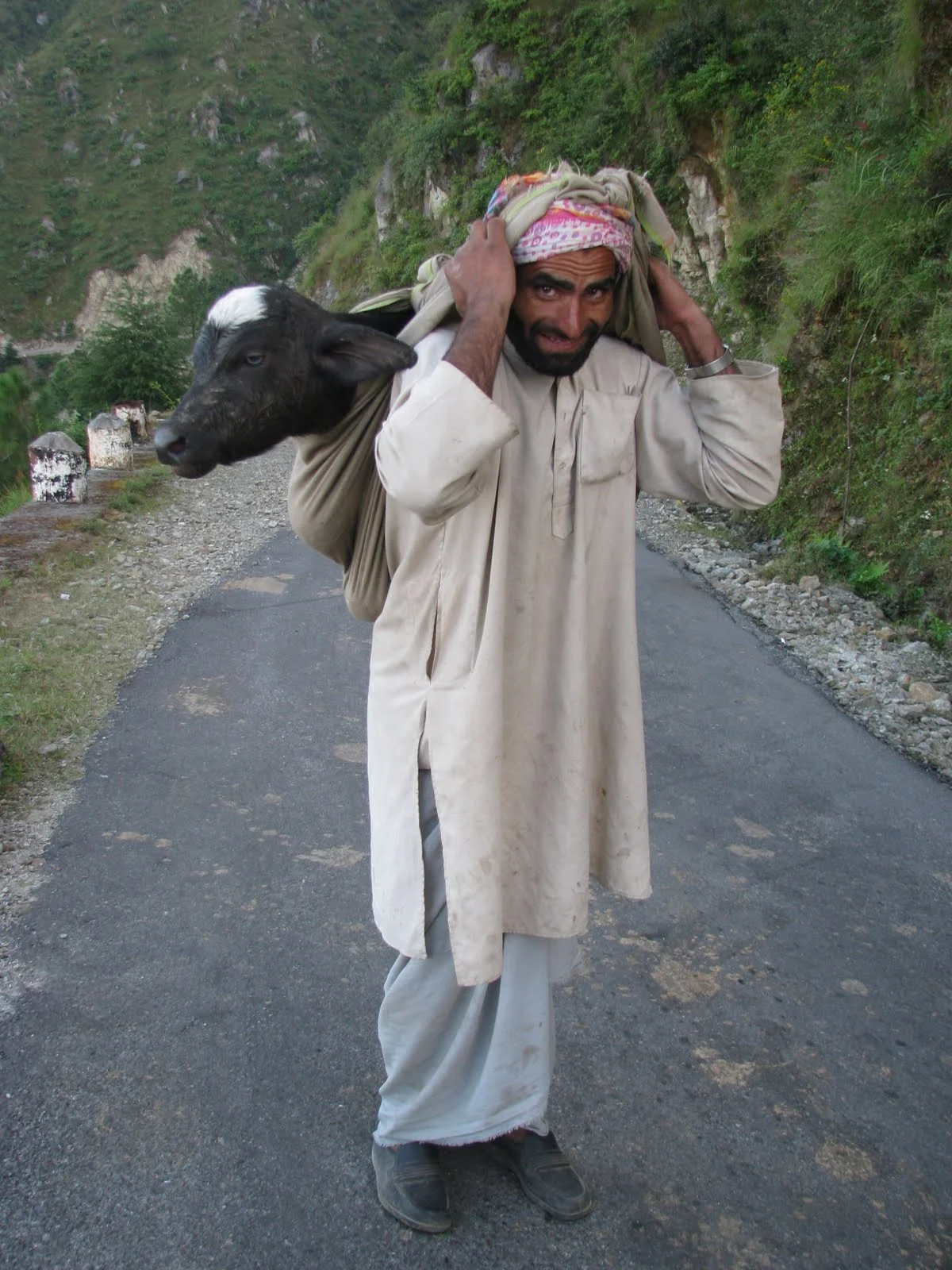

I walked with a caravan of Gujjars, a tribe that raises buffalo, on their autumn migration from the Dhauladhar range of the Himalayas to the plains of Punjab. Their migration follows the pastures, the availability of food for their buffalo. They move downhill at the end of the summer when the mountains get too cold, and return uphill when the plains get too hot. Migration takes 3 weeks, and they must rebuild their homes upon arrival (the structures are made of mud and do not last the season without maintenance). You can learn more about the Gujjars and see photos of the migration here (sadly, I lost my photos).

I evaluated the energy resources available to the Gujjars in their Himalayan village, at every camp along the migration route, and in their Punjabi village. By living and walking with a Gujjar family for 3 weeks, I was able to engage in ethnographic research methods such as participant observation and gain a deep appreciation for their everyday practices and challenges. I conducted many interviews along the way, and I returned to the community a few months later, after all the caravans had arrived, to conduct an energy needs assessment and hold more interviews and group discussions.

At the start of the project, I assumed that the Gujjars' greatest energy resource would be buffalo dung, and I thought some sort of portable biomass technology could be an interesting solution for them. However, I quickly learned that the buffalo dung is a source of income: people in rural India have many uses for bovine dung (fertilizer, fuel, construction, mosquito repellent), so Gujjars sell their dung to villagers. They preferred to earn this money rather than use the dung for energy.

Furthermore, I found that the Gujjars migrated at night. It is much easier for them to walk along paved roads than through the forest like they used to, but there is too much traffic for their buffalo during the day. But they don't have any source of light, and it can be very dangerous. After many interviews and group discussions with the nomads, I identified that a solar lantern could be a viable solution for their needs. They could charge the lanterns at their camps during the day (the camps are generally on the side of the road, not in the forest) and use them to guide their walk at night. When they reach their summer or winter destination, they can continue to use the solar lanterns to light their temporary homes.